[ad_1]

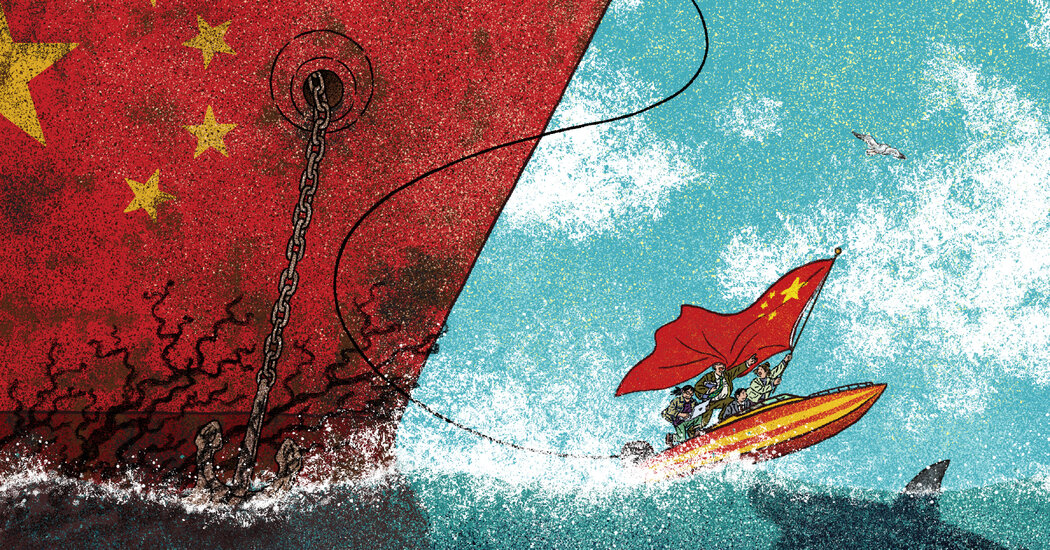

Two Chinas inhabit the American imagination: One is a technology and manufacturing superpower poised to lead the world. The other is an economy that’s on the verge of collapse.

Each reflect a real aspect of China.

One China — let’s call it hopeful China — is defined by companies like the A.I. start-up DeepSeek, the electric vehicle giant BYD and the tech powerhouse Huawei. All are innovation leaders.

Jensen Huang, the chief executive of the Silicon Valley chip giant Nvidia, said China was “not behind” the United States in artificial intelligence development. Quite a few pundits have declared that China would dominate the 21st century.

The other China — gloomy China — tells a different story: sluggish consumer spending, rising unemployment, a chronic housing crisis and a business community bracing for the impact of the trade war.

President Trump, as he tries to negotiate a resolution of a trade war, must reckon with both versions of its arch geopolitical rival.

The stakes have never been higher to understand China. It’s not enough to fear its successes, or take solace in its economic hardships. To know America’s biggest rival requires seeing how the two Chinas are able to coexist.

“Americans have too many imagined notions about China,” said Dong Jielin, a former Silicon Valley executive who recently moved back to San Francisco after spending 14 years in China teaching and researching the country’s science and technology policies. “Some of them hope to solve American problems using Chinese methods, but that clearly won’t work. They don’t realize that China’s solutions come with a lot of pain.”

Just like the United States, China is a giant country full of disparities: coastal vs. inland, north vs. south, urban vs. rural, rich vs. poor, state-owned vs. private sector, Gen X vs. Gen Z. The ruling Communist Party itself is full of contradictions. It avows socialism, but recoils from giving its citizens a strong social safety net.

Chinese people, too, grapple with these contradictions.

Despite the trade war, the Chinese tech entrepreneurs and investors I talked to over the past few weeks were more upbeat than any time in the past three years. Their hope started with DeepSeek’s breakthrough in January. Two venture capitalists told me that they planned to come out of a period of hibernation they started after Beijing’s crackdown on the tech sector in 2021. Both said they were looking to invest in Chinese A.I. applications and robotics.

But they are much less optimistic about the economy — the gloomy China.

The 10 executives, investors and economists I interviewed said they believed that China’s advances in tech would not be enough to pull the country out of its economic slump. Advanced manufacturing makes up about only 6 percent of China’s output, much smaller than real estate, which contributes about 17 percent of gross domestic product even after a sharp slowdown.

When I asked them whether China could beat the United States in the trade war, nobody said yes. But they all agreed that China’s pain threshold was much higher.

It’s not hard to understand the anxiety felt by Americans frustrated with their country’s struggles to build and manufacture. China has constructed more high-speed rail lines than the rest of the world, deployed more industrial robots per 10,000 manufacturing workers than any country except South Korea and Singapore and now leads globally in electric vehicles, solar panels, drones and several other advanced industries.

Many of China’s most successful companies have gained resilience from the economic downturn and are better prepared for the bad days ahead. “They’ve been DOGE-ing for a long time,” said Eric Wong, the founder of the New York hedge fund Stillpoint who visits China every quarter, referring to the Trump administration’s cost-cutting effort known as the Department of Government Efficiency. “By comparison, the U.S. has been living in excess for a long time.”

But as we marvel at China’s so-called miracles, it is necessary to ask: At what cost? Not just financial, but human.

China’s top-down innovation model, heavily reliant on government subsidies and investment, has proved to be both inefficient and wasteful. Much like the overbuilding in the real estate sector that triggered a crisis and erased much of Chinese household wealth, excessive industrial capacity has deepened imbalances in the economy and raised questions about the model’s sustainability, particularly if broader conditions worsen.

The electric vehicle industry shows the force of the two Chinas. In 2018, the country had nearly 500 E.V. makers. By 2024, about 70 remained. Among the casualties was Singulato Motors, a start-up that raised $2.3 billion from investors, including local governments in three provinces. Over eight years, the company failed to deliver a single car and filed for bankruptcy in 2023.

The Chinese government tolerates wasteful investment in its chosen initiatives, helping fuel overcapacity. But it is reluctant to make the kind of substantial investments in rural pensions and health insurance that would help lift consumption.

“Technological innovation alone cannot resolve China’s structural economic imbalances or cyclical deflationary pressures,” Robin Xing, the chief China economist at Morgan Stanley, said in a research note. “In fact,” he wrote, “recent advances in technology may reinforce policymakers’ confidence in the current path, increasing the risk of resource and capital misallocation.”

The Chinese leadership’s obsession with technological self-reliance and industrial capacity is not helping its biggest challenges: unemployment, weak consumption and a reliance on exports, not to mention the housing crisis.

Officially, China’s urban unemployment rate stands at 5 percent, excluding jobless migrant workers. Youth unemployment is 17 percent. The real numbers are believed to be much higher. This summer alone, China’s colleges will graduate more than 12 million new job seekers.

Mr. Trump was not wrong in saying factories are closing and people are losing their jobs in China.

In 2020 Li Keqiang, then the premier, said the foreign trade sector, directly or indirectly, accounted for the employment of 180 million Chinese. “A downturn in foreign trade will almost certainly hit the job market hard,” he said at the onset of the pandemic. Tariffs could be much more devastating.

Beijing is playing down the effect of the trade war, but as negotiators held talks last weekend with their U.S. counterparts, its impact was obvious. In April, Chinese factories experienced the sharpest monthly slowdown in more than a year while shipments to the United States plunged 21 percent from a year earlier.

All of the economic fallout will be shouldered by people like a man I spoke to, with the surname Chen, a former university librarian in a megacity in southern China. He asked that I not use his full name and where he lived to shield his identity from the authorities.

Mr. Chen lives in the gloomy China. He stopped taking the vaunted high-speed trains because they cost five times as much as a bus. Flying is often cheaper, too.

He lost his job last year because the university, one of the top ones in the country, was facing a budget shortfall. Many state-run institutions have had to let people go because many local governments, even in the wealthiest cities, are deeply in debt.

Because he’s in his late 30s, Mr. Chen is considered too old for most jobs. He and his wife had given up on buying a home. Now with the trade war, he expects that the economy will weaken further and that his job prospects will be dimmer.

“I’ve become even more cautious with spending,” he said. “I weigh every penny.”

[ad_2]

Source link